But while I have never thought of myself as especially adverse to admitting defeat when faced with compelling reasons to do so, just why, we might ask ouselves, should we start to think about licking our wounds right now (and why our wounds, since it is poor old Latvia which has been subjected to all the blood-letting implied by this none-too-convincing "thought experiment" turned reality)?

Well, in the first place, given the dramatic current account correction, Latvia's outlook has been revised from negative to stable by Standard and Poor's rating agency, which means - when you get down to the nitty gritty - that they don't expect any further downward revisions in Latvia's sovereign credit rating in the next six months.

Standard & Poor’s, a rating agency, has raised its outlook on Latvia’s debt from negative to stable (ie, it no longer expects further downgrades). The current account, in deficit to the tune of 27% of GDP in late 2006, is in surplus. Exports are recovering. Interest rates have plunged and debt spreads over German bonds have narrowed (see chart). Fraught negotiations with the IMF and the European Union have kept a €7.5 billion ($10 billion) bail-out on track, in return for spending cuts and tax rises worth a tenth of GDP.And anyway, Latvia is not as bad as Greece.

Even so, Latvia looks good when compared with Greece. It did not lie about its public finances or use accounting tricks. Strikes have been scanty. Protests are fought in the courts, not the streets. Both Greece and Latvia have had hard knocks, but Greeks became used to a good life that they are loth to give up. Latvians remain glad just to be on the map.As evidence for just how much better Latvia is doing than Greece the Economist cite the movements in the respective bond spreads, and of course, the extra interest the Greek government has to pay to raise money (with respect to equivalent German bonds) is now marginally more than the extra interest Latvia has to pay, but then Greece has yet to go to the IMF.

But just in case both these arguments seem rather like clutching at straws when compared to the "gravitas" of the situation, there is a "clincher".

"despite a fall in GDP last year of 17.5%, Latvia seems to have achieved

something many thought impossible: an internal devaluation. This meant regaining competitiveness not by currency depreciation but by deep cuts in wages and public spending. In a recent discussion of Greece, Jörg Asmussen, a German minister, praised Latvia for its self-discipline".

Well, I'm sure that having a positive reference from a German minister in a discussion on Greece is a positive sign, but hang on a minute: just what internal devaluation is our author talking about here, and what deep cuts in wages and salaries? According to the latest available data from the Latvian Statistics Office, average wages in Latvia were down 10% in September 2009 over 2008, but since wages in September 2008 were up 6.5% over wages in September 2007, when the Latvian economy was already in deep trouble and wages and prices were already seriously out of line, then they have only actually fallen back some 4.15% over the two year period. I am sure these cuts are painful (a 20% unemployment rate, and young people emigrating is even more painful), but I would hardly call this a "deep cut" yet awhile.

The thing to remember here is the difficult characterists imposed by the presence of a peg. Latvian real wages (when adjusted for inflation) may well have fallen more, but this is to no avail (and simply makes the internal consumption problem worse), since what matters are the Euro equivalent prices of Latvian wages and exports. This is one of the reasons why in these circumstances a peg is such a horrible thing.

And if you're still not very convinced, let's try the Eurostat equivalent data for average hourly wage costs, which had in fact only fallen by 3.5% year on year in the third quarter of 2009.

Why the difference between average wages and average hourly labour costs? Well, given the depth of the recession people are obviously earning less, since they are working less, but this doesn't help overall competitiveness, since what matters here is the hourly cost of each unit of labour. I'm sorry if this is all fairly turgid economic data stuff (yawn, yawn, yawn) but if you want to cry victory, you really do need to check your facts a bit first.

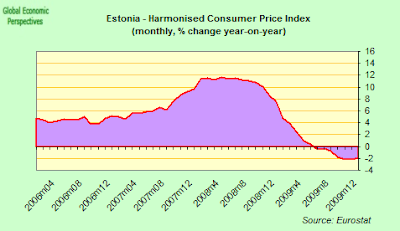

In fact, as I said in my last post, additional evidence from the consumer price index suggests the "internal devaluation" is only working at a hellishly slow pace. Prices were only down by 3.3% in January 2010 over January 2009 according to the latest HICP data from Eurostat.

And while producer prices have fallen a little further - by 6.6% in January over January 2009 - there is still a long long way to go.

Basically there is no doubt that Latvia's great economic fall may be coming to an end, but as I explained in this post here, that is not the same thing at all as resuming growth. To get back to growth Latvia's internal devaluation needs to be driven hard enough and deep enough to generate a sufficient export surplus to drive headline economic growth at a sufficient speed to start creating jobs again. This is not about a fiscal adjustment, it never was, and it is little consolation for Latvia to be compared with Greece and told that they are doing just that little bit better. Cry Victory we are told, and unlease the jobs of war. Would that things were as easy done as said!