Facebook Blogging

Edward Hugh has a lively and enjoyable Facebook community where he publishes frequent breaking news economics links and short updates. If you would like to receive these updates on a regular basis and join the debate please invite Edward as a friend by clicking the Facebook link at the top of the right sidebar.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

The Social Impacts of the Economic Slowdown: The Latvian experience

Guest Post by Eliana Marino

The economic and financial crisis that started in 2008 seems to be on its way to being overcome by many EU member states, but the population in some of the most touched countries is still labouring under the ongoing effects of the slowdown. Latvia, which underwent an annualised decline of 18% of GDP in the first quarter of 2009 and still has the highest unemployment rate in the EU, is experiencing a veritable revolution in its population structure and is preparing to face serious demographic challenges.

The strong recession experienced in the last few years has sadly confirmed the high propensity of Latvian people to migrate for economic reasons and generated a real “exodus” of working age population.

Before 1999, a peak of emigration was registered due to the endogenous migration potential of the collapsed Soviet Union, but, from 1999 to 2002 the outflows seemed to stabilize and to show a slowing trend. This trend changed with the accession to the European Union and the immediate application of the free movement of labour by UK, Ireland and Sweden, which decided to open their borders to New Member States immigrants without any transitional restrictions. These conditions created an increase in the number of emigrants in 2006 and the “old” member states definitely replaced the Russian Federation and the ex Soviet Republics as main countries of destination.

The decline of the outflow in 2007 is linked to Latvian extraordinary economic growth which appeared to guarantee an increase in the wellbeing of the population. This situation started to deteriorate in the second half of 2008, generating a new rise in emigration decisions and increasing more and more in the following year.

Net migration has always been negative and, combined with a Total Fertility Rate among the lowest in EU, it strongly contributed to a progressive and continuous decline of the total population.

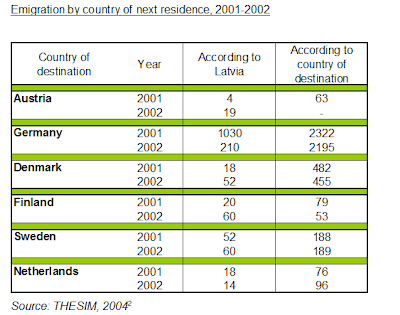

Official data, as analyzed above, cannot provide a real portrait of migration dynamics in Latvia. While the registration of immigrants is enough reliable due to the strict controls at the external borders of the EU, emigration statistics are completely unreliable because the large majority of emigrants did not declare its departure and no alternative method is adopted to catch up their real number. The gap between registered and factual data is showed by the comparison with statistics provided by the destination countries, as showed in the graph below:

More recent data were collected through the EU funded project The Geographic Mobility of the Labour Force , consisting of a survey conducted in 2007. The study arrived at the conclusion that a bit more than 40˙000 people emigrated between 2004 and 2005 (87% more than registered data). The authors forecasted that intensive emigration was expected to continue and that, looking at the number of respondents who said that they wonted to leave and at those who already did something in pursuit of this dream, by 2010 between 10˙000 and 16˙000 people were supposed to leave Latvia, thus totaling 50˙000 to 80˙000 emigrants from 2004 to 2010.

These estimates were presented in 2007 when Latvia was going through a period of sustained economic growth and no one could even imagine the economic collapse which the country is undergoing in this moment.

The survey, which I personally conducted in Riga from September to December 2009 and which involved some of the major Latvian experts on migration issues, showed that around 30,000 people are supposed to have left Latvia in 2009 and the same number is forecasted also for 2010.

These massive emigration flows from Latvia can strongly affect the future demographic and economic structure of the country, creating serious problems of labour shortage, unsustanability of the pension system and huge population decline.

Since the years of great economic growth, Latvia experienced a huge problem of labour shortage due not only to the lack of high skilled professionals but also to the general discrepancy between demand and offer of labour. In 2006-2007 this situation was one of the main topics of political and public debate and, under the pressures of the enterprises, the government approved a more liberal immigration policy in order to select labour force from abroad.

The downturn of 2008 caused an inversion of the trend: enterprises were obliged to reduce the labour force and the employment rate decreased together with the level of wages. These elements represented the main push factors for emigration and they are currently generating a real “exodus” of the labour force, creating dangerous structural problem in Latvian economy. Actually, lack of labour and especially of high skilled professionals will be a veritable challenge for the economic recovery of the country and nowadays it is one of the main reasons of concern for Latvian politicians and intellectuals.

From the demographic point of view, the impact of emigration can be considered under two different aspects:

- emigration of working age population makes the demographic burden increase: the number of inactive people (children and retired people) exceeds the number of active people, creating serious challenges for the sustainability of the welfare system;

- the most part of the outflows consists of working age population (from 15 to 65 years old) that includes people in reproductive age (from 15 to 49 years old). A huge number of emigrants in this particular age group means a further reduction of the natural increase of the population. In fact, they will probably have their children abroad or the migration decision itself will discourage the creation of numerous families.

This situation has to be combined with the low levels of Total Fertility Rate which characterize the country since more than 20 years ago. In Latvia, the first demographic transition to a rational regime of reproduction began at the end of XIX Century and the total fertility rate was lower than the replacement level already in the second half of the Century, due to repressions and harsh living conditions during the wars and the Soviet occupation. The replacement level was met only in the 80s after the introduction of partially paid child birth leave. Since then, the birth rate has decreased to unprecedented level and has represented an issue of serious concern for Latvian government. In particular, the decline of total fertility rate accelerated during the economic and political transition, since the Soviet centralized welfare collapsed and the national government opted for a shock therapy instead of a gradual and progressive transition to the market economy.

However, Latvian government recognised the need to ensure reproduction of the population as a prerequisite for the nation’s existence and started to evaluate adequate tools for family support. The adoption of successful family policies made the birth rate level stabilize since 1999 and start to increase at the beginning of the XXI Century. Anyway, the total fertility rate never reached the replacement level and it is still among the lowest in the EU (average 1.4 children per woman in the period 2005-2010 ).

As a consequence of these indicators, Latvian population dropped from 2.5 to 2.2 million people in 15 years and the negative growth rate is expected to accelerate in the next years.

The experts interviewed in the last months of 2009 proposed different solutions to both economic and demographic challenges but they agreed on the fact that a more liberal immigration policy might be really helpful to solve problems of labour shortage and pension sustainability as well as to contribute to the inversion of the negative demographic trends. However, this proposal, which is one of the main topic of public debate since the economic boom, is in direct conflict with the hostility of national population toward immigrants. Latvian critical historical experience with integration of different ethnicities is the clearest explanation of this hostility and probably some years are still needed to overcome these cultural barriers.

In definitive, the results of the survey allow to conclude that Latvia needs some important structural reforms (concerning an efficient social policy, a comprehensive population policy, a strong action against corruption and a reduction of the bureaucratic burden) to be implemented by the national government in order to prepare the country to play its role at the European and international level and to take the best advantages from the opportunities provided by the integration and globalization process. The first step to achieve this objective is the promotion of a cultural change whose main goal is to dump the “dependency from the past” and to open mental and factual borders to modernity.

Footnotes

1/ Latvija Statistika (Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia), www.csb.gov.lv, accessed on April 17th 2010

2/ Herm A. et Al, THESIM-Toward Harmonised European Statistics on International Migration, Country Report Latvia, Sixth Framework Programme, priority 8.1: Policy Oriented Research, Integrating and Strengthening the European Research Area, December 2004

3/ Krišjāne Z. et Al., The Geographic Mobility of the Labour Force, National Programme of European Structural Funds “Labour Market Research”, project “Welfare Ministry Research”, University of Latvia, co-financed by the European Union, 2007

4/ Eglīte P., National Policy for Increasing the Birth Rate in Latvia, in Humanities and Social Sciences Latvia, University of Latvia, Institute of Economics-Latvian Academy of Sciences, 2008

5/ UNdata, www.data.un.org accessed on January 30th 2010

Latvia: Living in the Land of Extremes

Guest Post by Morten Hansen, Stockholm School of Economics in Riga

Here in Latvia the internal devaluation continues and the debate is whether the economy is flexible enough for this experiment. I say perhaps it is, Edward says perhaps it isn’t but one thing is for sure: the Latvian economy is (possibly perversely) indeed flexible.

I would like to illustrate this point with a series of numbers for the extremes that we have witnessed in Latvia so in the following I list a series of macroeconomic variables and the times at which they were at their extremes during the boom and during the current bust. After that I try a little discussion of why the development was so extreme here.

Numbers are from the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia and from the Bank of Latvia, I use monthly data when I can, otherwise quarterly. All growth rates are y-o-y.

GDP growth – from the biggest increase in the EU to the biggest decline

2006 Q3: +12.7%

2009 Q3: –19.1%

Inflation – the highest inflation rate in the EU becomes the biggest rate of deflation in less than two years

2008 V: +17.9%

2010 II: –4.2%

Wage growth – again both are extremes also in an EU context

2007 Q3: +32.9%

2009 Q4: –12.1%

Unemployment rate (among 15-64 years)

2007 Q4: 5.4%

2010 Q1: 20.7%

Current account (% of GDP) – has anyone ever seen a +40 percentage point turnaround in the current account balance in less than three years?

2006 Q4: –27.2%

2009 Q2: +14.2%

Credit growth, households

2003 VIII: +85.8% (an early spike but growth rates in excess of 60% continued for several years)

2010 IV: –5.1%

Credit growth, firms

2006 II: +54.7%

2010 III: –7.9%

Money supply growth (M2)

2006 X: +43.9%

2009 VIII: –12.5%

Closely linked to the three latter sets of statistics one can note that house prices dropped some 53% in 2009, see here p. 6, again the largest decline in the EU, while several years during the boom had recorded increases around 60% y-o-y.

But one variable hasn’t changed and here I am of course thinking of the exchange rate which remains at a parity of 0.702804 LVL/EUR and is managed in a narrow +/–1% band. Those who follow Latvia will know, however, that there were great market uncertainties surrounding the peg first in March 2007 then in November 2008 (at the time of the nationalization of Parex Bank) where 10-14 November was the week with the biggest ever intervention by Bank of Latvia, which sold 267.65 mill. EUR. Altogether mid-November – mid-December saw a loss of some 18% of foreign reserves – more details on interventions here. In terms of interest rates the June 2009 scare saw the overnight interbank rate (RIGIBOR) peak at 33% on 26 June.

Latvia is not the only country with a credit boom, with a housing boom or with problems of overheating but one may ask why it was so violent here, why almost all numbers were and are more extreme. I shall try to provide some explanations below.

1. The Latvian credit boom was not just a boom, it was more of an avalanche as it represented the emergence of the financial sector. Whereas loans to individuals and enterprises constituted some 16% of GDP in 2000 this reached 91% of GDP in 2008 X, when loans saw their peak.

2. There was a naïve belief in rapid income convergence both among politicians (see this story from the Baltic Times in 2006 where a goal was formulated by Latvia’s First Party to raise Latvia’s standards of living to those of Ireland in ten (!!!!!) years….). This belief must at least to some extent have been shared by the banks since it can explain why they provided large loans compared to actual income.

3. The belief – or certainly the hope thereof – was strong among ordinary people, too. For decades during Soviet rule most had been denied the possibility of one’s own flat or car. Thus it is not surprising that when something called a loan appears as a possibility, many took it. One may also call it the result of a financially uneducated people which is not to say that such do not exist elsewhere, just look at the subprime market in the US or Brits (and others) buying summer houses in Bulgaria or Turkey.

4. Latvia’s fiscal policy was highly procyclical during the boom thus exacerbating this boom; major consolidation efforts now act as similar procyclical fiscal policy, this time exacerbating the bust.

5. Too late (2007) Latvia introduced a credit register – there is a story about one person who managed to borrow from no fewer than 25 different banks….

6. Latvia has many more banks than Estonia or Lithuania and this perhaps led to more aggressive and less prudent lending to keep up market shares.

7. Some also suggest that due to the attractiveness of Riga and its seaside resort/city Jurmala to people from Russia even more froth was created in the Latvian real estate market.

8. The public economic-political debate was poor in the ‘fat years’ and it was somehow ‘unpatriotic’ to argue that problems were building up.

9. And, lastly and more speculative, but I could imagine that some of the Swedish and other foreign banks that entered brought with them a perception at the subconscious level of the Latvian market being similar to their home markets in terms of customers’ realism and honesty, features that were not always met. Some customers had unrealistic expectations of their future pay (but can you really blame them when wages were growing in excess of 30% a year?), some were most likely dodgy customers from the outset and the banks were a tad naïve. I am speculating but from conversations with bankers I am also sure I am right….

And in the end one may just wonder what the total cost of miscalculations due to an environment of extreme macroeconomic uncertainty has been for individuals, enterprises, banks and the public sector.

To end on a lighter note: At the time of writing the outdoor temperature is +32° (90F), which is hot here. Less than half a year ago we had temperatures down to –30° (–22F) so Latvia is not just extreme with respect to economic indicators.

Here in Latvia the internal devaluation continues and the debate is whether the economy is flexible enough for this experiment. I say perhaps it is, Edward says perhaps it isn’t but one thing is for sure: the Latvian economy is (possibly perversely) indeed flexible.

I would like to illustrate this point with a series of numbers for the extremes that we have witnessed in Latvia so in the following I list a series of macroeconomic variables and the times at which they were at their extremes during the boom and during the current bust. After that I try a little discussion of why the development was so extreme here.

Numbers are from the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia and from the Bank of Latvia, I use monthly data when I can, otherwise quarterly. All growth rates are y-o-y.

GDP growth – from the biggest increase in the EU to the biggest decline

2006 Q3: +12.7%

2009 Q3: –19.1%

Inflation – the highest inflation rate in the EU becomes the biggest rate of deflation in less than two years

2008 V: +17.9%

2010 II: –4.2%

Wage growth – again both are extremes also in an EU context

2007 Q3: +32.9%

2009 Q4: –12.1%

Unemployment rate (among 15-64 years)

2007 Q4: 5.4%

2010 Q1: 20.7%

Current account (% of GDP) – has anyone ever seen a +40 percentage point turnaround in the current account balance in less than three years?

2006 Q4: –27.2%

2009 Q2: +14.2%

Credit growth, households

2003 VIII: +85.8% (an early spike but growth rates in excess of 60% continued for several years)

2010 IV: –5.1%

Credit growth, firms

2006 II: +54.7%

2010 III: –7.9%

Money supply growth (M2)

2006 X: +43.9%

2009 VIII: –12.5%

Closely linked to the three latter sets of statistics one can note that house prices dropped some 53% in 2009, see here p. 6, again the largest decline in the EU, while several years during the boom had recorded increases around 60% y-o-y.

But one variable hasn’t changed and here I am of course thinking of the exchange rate which remains at a parity of 0.702804 LVL/EUR and is managed in a narrow +/–1% band. Those who follow Latvia will know, however, that there were great market uncertainties surrounding the peg first in March 2007 then in November 2008 (at the time of the nationalization of Parex Bank) where 10-14 November was the week with the biggest ever intervention by Bank of Latvia, which sold 267.65 mill. EUR. Altogether mid-November – mid-December saw a loss of some 18% of foreign reserves – more details on interventions here. In terms of interest rates the June 2009 scare saw the overnight interbank rate (RIGIBOR) peak at 33% on 26 June.

Latvia is not the only country with a credit boom, with a housing boom or with problems of overheating but one may ask why it was so violent here, why almost all numbers were and are more extreme. I shall try to provide some explanations below.

1. The Latvian credit boom was not just a boom, it was more of an avalanche as it represented the emergence of the financial sector. Whereas loans to individuals and enterprises constituted some 16% of GDP in 2000 this reached 91% of GDP in 2008 X, when loans saw their peak.

2. There was a naïve belief in rapid income convergence both among politicians (see this story from the Baltic Times in 2006 where a goal was formulated by Latvia’s First Party to raise Latvia’s standards of living to those of Ireland in ten (!!!!!) years….). This belief must at least to some extent have been shared by the banks since it can explain why they provided large loans compared to actual income.

3. The belief – or certainly the hope thereof – was strong among ordinary people, too. For decades during Soviet rule most had been denied the possibility of one’s own flat or car. Thus it is not surprising that when something called a loan appears as a possibility, many took it. One may also call it the result of a financially uneducated people which is not to say that such do not exist elsewhere, just look at the subprime market in the US or Brits (and others) buying summer houses in Bulgaria or Turkey.

4. Latvia’s fiscal policy was highly procyclical during the boom thus exacerbating this boom; major consolidation efforts now act as similar procyclical fiscal policy, this time exacerbating the bust.

5. Too late (2007) Latvia introduced a credit register – there is a story about one person who managed to borrow from no fewer than 25 different banks….

6. Latvia has many more banks than Estonia or Lithuania and this perhaps led to more aggressive and less prudent lending to keep up market shares.

7. Some also suggest that due to the attractiveness of Riga and its seaside resort/city Jurmala to people from Russia even more froth was created in the Latvian real estate market.

8. The public economic-political debate was poor in the ‘fat years’ and it was somehow ‘unpatriotic’ to argue that problems were building up.

9. And, lastly and more speculative, but I could imagine that some of the Swedish and other foreign banks that entered brought with them a perception at the subconscious level of the Latvian market being similar to their home markets in terms of customers’ realism and honesty, features that were not always met. Some customers had unrealistic expectations of their future pay (but can you really blame them when wages were growing in excess of 30% a year?), some were most likely dodgy customers from the outset and the banks were a tad naïve. I am speculating but from conversations with bankers I am also sure I am right….

And in the end one may just wonder what the total cost of miscalculations due to an environment of extreme macroeconomic uncertainty has been for individuals, enterprises, banks and the public sector.

To end on a lighter note: At the time of writing the outdoor temperature is +32° (90F), which is hot here. Less than half a year ago we had temperatures down to –30° (–22F) so Latvia is not just extreme with respect to economic indicators.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)