By Claus Vistesen: Copenhagen

Even when liars tell the truth, they are never believed. The liar will lie once, twice, and then perish when he tells the truth.

One thing which is certain at the moment is that the rumour mill is grinding hard and that it is very difficult to get a clear picture of what is going on. It is too cumbersome for me to go into the entire background here (I assume most of you are familiar with the Baltic and CEE situation), but if you want some background try this or this which will give you the opportunity to browse a myriad of articles. The situation is however pretty simple. Ever since it became clear that the Baltics was going to suffer not only a hard landing, but a veritable collapse on the back of the financial crisis one obvious question always was whether these economies could maintain the Euro peg throughout the correction process. So far the peg have held and the countries, as well as the IMF who have been called for aid, have been committed to the peg and thus the future entry in the Eurozone.

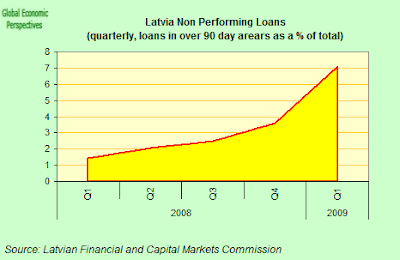

But this has come at a price and as international economics 101 tells us, the only way you can correct with a fixed exchange rate and an open external account is through deflation and a very sharp drainage of domestic capacity. And so it has come to pass that particularly in Latvia who has come under the receivership of the IMF the scew has been turned, (and turned and turned) and now the question is how much more can the public and the goverment take. In a recent article in the NYT the situation is well described as the Latvian government scrambles to meet ends on the IMF's pre-condition to continue funding the bailout programme.

One very significant indication that things are near its breaking point came when Central Bank Governor Ilmars Rimsevics launched the idea that, since the liquidity in Lati is being drained in order to keep the peg and because the cuts needed to abide by the IMF rules are immense, public employees might be submitted to receive their pay in "vouchers" in stead of actual Lati. As Edward points out, this is straight out of the vaults of the Argentian crisis' annals. This is one of the things you get with a peg maintained too tightly during a deflationary crisis. It deprives you from liquidity. Now, in some sense this all about the next installment of IMF funds of course and whether Latvia will (can) make the needed budget cuts to please the fund to such an extent that they will continue to slip the bailout checks in the mail.

Essentially, under the peg, the central bank has to buy Lati in the open market to maintain the peg since there is, naturally, a pressure on the peg as everybody want's euros. So, the central bank is forced to drain the economy from liquidity to maintain the peg in an environment where the economy is contracting at about 20% over the year. This is not fun and, as it were, not sustainable given the trajectory of these economies. In this sense devaluation is no cure but a simple prerequisite (and necessity) for the healing process to begin.

Even more significant it appears that the the foreign banks, so important in the Baltic story since they basically provided the liquidity inflows to fund the boom, are beginning to accept the basic point I, and others, have made so often before. This is the point that although a devaluation would entail default on a large batch of Euro denominated loans, this default would come in either case as a result of the utterly horrid contraction. In this sense it was very significant that the SEB Chief Executive Annika Falkengren pointed out;

"In total we would have the same size of credit losses, but (if there is no devaluation) they would be a little more regular and over a longer time frame," SEB Chief Executive Annika Falkengren told Swedish radio. "In the case of a devaluation they would be pretty much instantaneous."

This is important because one prerequisite for the peg to hold was always that the foreign banks explicity backed it since they pretty much finance the majority of the credit needed to hold these economies afloat and particularly so Latvia. Essentially, on the Swedish side of things it appears that they are pretty much treating this as over and done.

According to Dagens Industri' Torbjörn Becker, leader of the Eastern European Institute of the School, a devaluation is likely. "The alternative to a devaluation in Latvia is to wait until the reserve is drained and the economy will disappear into a black hole, " he told the DI. Torbjörn Becker believe that neighbors Estonia and Lithuania follow.

Moreover, the Riksbank just recently bolstered its foreign currency reserve with an amount equal to 100 mill SEK which can be interpreted as a precautionary measure to deal with a potential fallout in the Baltics.

The Executive Board of the Riksbank has decided to restore the level of the foreign currency reserve by borrowing the equivalent of SEK 100 billion. This needs to be done because the Riksbank has lent part of the foreign currency reserve to Swedish banks. We have also increased our commitments to other central banks and international organisations. The Riksbank needs to maintain its readiness to supply the Swedish banks with the liquidity required in foreign currency.

Finally, there is Danske Bank, aka Lars Christensen in the context of the CEE, who warns of a serious event risk in the Baltics in today's daily installment on emerging markets.

The event risk has risen sharply in the Baltic markets and we advise outmost caution. Yesterday, the Swedish central bank Riksbanken said it will increase its currency reserve by SEK 100 bn through a loan from the Swedish debt agency. Investors seem to believe that this is a buffer to deal with potential problems arising from the Baltic crisis.

(...)

With worries over the Baltic situation on the rise there is a significant risk of negative spill-over to other markets in CEE. Therefore we see clear downside risk on the CEE currencies and a risk of a sharp sell-off in the CEE fixed income markets in the coming days. We especially see value in buying USD/HUF, but potentially also USD/PLN on an escalation of the Baltic crisis.

Basically, the way I see it is that there is only so much the currency boards can do and in Latvia's case, after having already spent over 500 million euros buying lats, I think we are moving steadily towards the end game. Of course, there is an obvious risk that I will perish further down the road with this one, but then again, so be it. It is imperative that investors and stakeholders entertain the possibility of a multiscale Baltic devaluation and, obviously, a sharp CEE sell off in the wake.